ABOUT LEAH

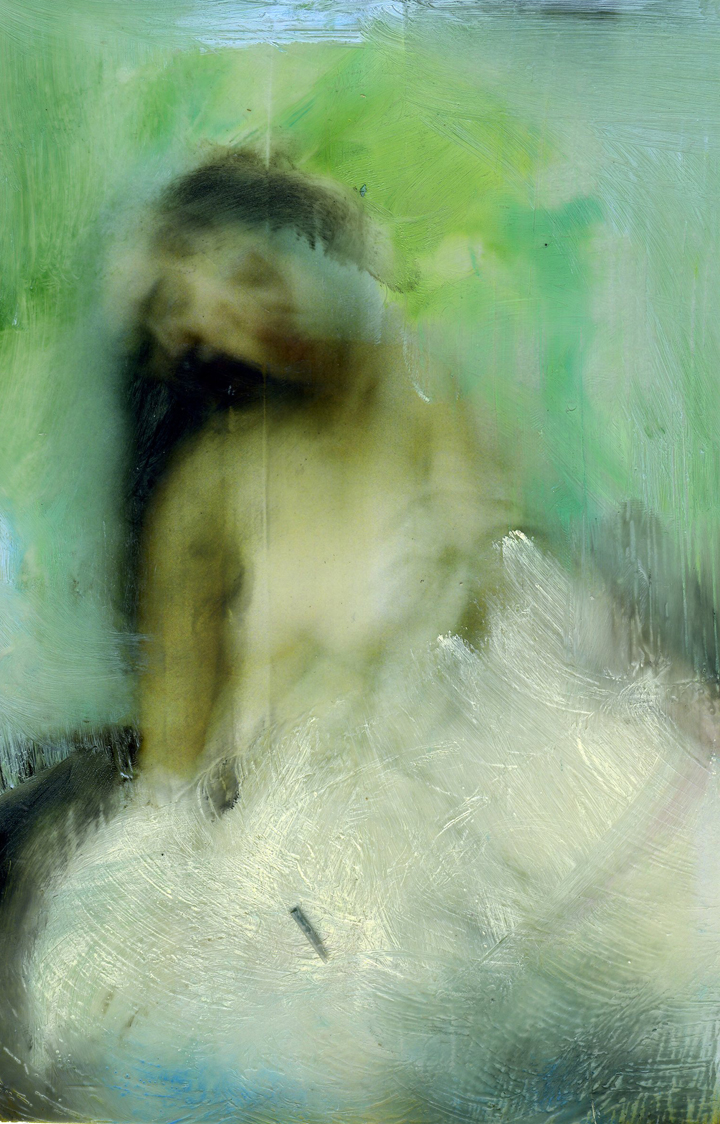

Leah Macdonald makes her portraits into artifacts, one-of-a-kind conceptions that suggest the imperfection and multiplicity of memory. The heart of her mixed media work, a poignant sense of revisitation and return. Her passion is sharing her art and creativity with others through teaching workshops, art exhibitions and her prolific internet portfolios. Her new technique “photogestic” is the fruition of all her years of experimenting with altered surface analog photography and mixing media. It combines her three skills in art: photography, collage and encaustic painting. When transforming photographs from slivers of reality to complete fantasy, she expresses the tales of womanhood. She uses collage to place her figures in new and surreal environments. Her intuition with encaustics allows beeswax to embellish and veil her models. She carefully draws on the wax to decorate and control the visibility of the subject. Layering these mediums by manipulating surface texture and color grants her the ability to express her imagination and bring her art vision to life.

She was born in Philadelphia, she attended college in San Francisco and then went on to receive her MFA in Photography from the California College of Art. She enjoyed a long and varied career path within the arts:commercial photography, professional analog printer and college professor. She was the Education Curriculum Director at the Manayunk-Roxborough Art Center. In 2007 she was asked to do a live encaustic painting demonstration on the Martha Stewart show. Other highlights include a solo retrospective of encaustic nudes at Wexler gallery in 2010. In 2016 she was the scenic director of In My Body Musical. In 2017 she was selected as the recipient of the New Courtland Fellowship by The Center for Emerging Visual Artists.In 2018 she was an artist in residence at the Encaustic Castle. She recently launched a new website; Lost Light Luv, it features her legacy analog photography. Her encaustic photography art is represented by Inliquid Arts, Saatchi Art, Galerie BMG and Cerulean Art Gallery in Philadelphia. She has also self published numerous handmade artist books.

ABOUT LEAH’S WORK - written by Kirsten Kaschock

Wax preserves while it obscures. In this way, it is like memory.

The body records trauma, sometimes as visible scars, as bruises that fade, sometimes in its posture and line, a change of attitude or mood, or a staining—a coloration. Twenty years ago, after a devastating motorcycle accident, Leah Macdonald advertised for photographic models, women who “had experienced trauma.” At the same time, she first incorporated beeswax into a single image in her thesis at California College of the Arts, beginning an exploratory dialogue between encaustics and photography (primarily black-and-white images on silver gelatin paper) that allows her to bring to the surface the dreamt world. The camera opens into a moment, like a cracked door, and Macdonald pushes through to the emotional landscape behind.

Several of the artists Macdonald claims as inspiration and antecedents (Deborah Turbeville, Ellen Rogers, Lillian Bassman) have in common a world-making quality to photographs that center on the female form. There is implied narrative, but also a specifically feminine brand of voyeurism: a glimpse, through the figure, into a subject’s inner life that also/always doubles for the photographer’s. All the while, we are reminded that the glimpse is just that—the merest sliver of a complex and layered reality only partially available to the viewer. A window onto a window.

In his treatise on photography, Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes suggests that what holds a spectator’s photographic interest is a detail that acts like a wound—the punctum. Barthes suggests that it reaches out from the work as a whole to pierce the viewer. He writes of the punctum, “...whether or not it is triggered, it is an addition: it is what I [the spectator] add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there.” Macdonald, by intervening between image and viewer, by developing the photograph through collage and the addition of wax (which she paints, scrapes, sculpts, layers, and stencils), heightens this experience of wounding by suggesting the processes that happen after trauma. Healing, forgetting, fragmentation, re-membering, acceptance, re-incorporation. By inserting her own body and its labor between the time of the photograph and our receiving it—she makes her portraits into artifacts, one-of-a-kind conceptions that suggest the imperfection and multiplicity of memory. This recursivity is at the heart of her mixed media work, a poignant sense of revisitation and return.

Wax, like the body itself, is responsive and mutable, changed by pressure and temperature, recording what has been done to it. Wax tablets were used for writing in ancient Greece. These book forms, made of two frames bound together with wax filling their reservoirs, were portable and reusable, able to be erased by rubbing, and then rewritten. Macdonald uses the reproductive nature of photographs not in order to create exact replicas, but to make new versions... each one singular... each suggesting a different entry point into the image... a different way of seeing or conceiving. The fact-ness of the photograph is both emphasized and questioned. The same picture is not the same. Macdonald says, “A stained photograph and a ripped corner speak of life’s lessons. Each mistake is ultimately important to me.” The image, marked by accident or conscious violence or serendipity, is written upon again through the accretion of different wax skins and Macdonald’s manipulation of them—the evidence of the artist, the artist’s body, the impression, the trace.

Iconic fashion photographer, Lillian Bassman, once said she turned from painting to photography because “I discovered I could ‘paint’ more expressively in a darkroom.” Her darkroom techniques of bleaching, burning, and selective focus abstracted the female forms she worked with into mood-saturated portraits. As technology has lessened the photographer’s need for and access to the darkroom, Macdonald has re-envisioned the concept of intense processing through her encaustic work, and the texture added makes its effects distinct from two-dimensional alterations. The work has depth, an underwater luminosity that changes as we move around it. It has a sculptural feel, inviting the eye to skim across its physical surface as with a painting. There is an eroticism to wax, a tactile invitation that is also a barrier between viewer and image. Imperfections are part of the beauty, its singularity, its hauntedness.

Macdonald’s work abstracts through the creation of palimpsests. Like viewing the interior of a house through gauze, or the next page of a book through a velum layer of handwriting, emphasis is achieved through mystery, shadow, hiddenness. It should come as no surprise that Macdonald is also a bookmaker; her love of paper, texture, and language are underscored in that work. What narrative is present in her images has this sense of book-ness—her images can seem singular pages of fleeting beauty taken from some dark fable. Her figures have stories that range before and after these moments, and those stories are somehow contained within the single image. If, as Diane Arbus once said, “a photograph is a secret about a secret,” then Macdonald’s work is a secret upon a secret. The levels interact to comment on one another, and the interplay between them can be harmonious or dissonant, obscuring or revelatory.

The nudes she has photographed for decades are vulnerable to scrutiny. Yet the interior world presented in Macdonald’s work resists knowability—narratives suggested are left untold. Where the photographer Duane Michals offers discrete sequences that direct us through time... Macdonald work is non-linear. The past exists within the image, recorded on the body but also within the distance between the viewer and the subject, time recorded in the encaustic veils Macdonald has placed between us and the figure. In some new work, she has taken that semi-opacity a step further by abstracting figure into flower.

Recently, the balance between image and encaustics has shifted and a new subject matter is surfacing in Macdonald’s work. Capturing impressionistic suggestions of leaves and blooms in layers of wax, echoing their form in beeswax stencil, overlaying photographs with floral patterns like tinted lace curtains, Macdonald’s evocation of flowers is pushing her consideration of color in new directions, and foregrounding the contradictory tensions that have defined her work since the beginning. She writes of one of her earliest memories: “When I was a child I would catch fireflies in a jar and cover the jar lid with foil, punch little holes in the top of the jar and then sit in the dark of my closet and watch them flicker on and off until they died.” This interaction with and mutilation of the natural world was Macdonald’s first dark room, an attempt to capture beauty and light that ended up teaching her lessons about “joy and tragedy” and “intimacy and exile” that persist.

The artist’s interference in the world is what makes of the world art, but always that interaction causes friction. In Macdonald’s work, black-and-white photography reduces an image to contrast and line. Then wax and paint re-introduce color in a manner invoking memory. Stencils and floral patterning both distract the eye and create background against which an image comes into focus—as the wax and the materials beneath it vie for attention. Since the tapestry makers of the middle ages, flowers have served artists as both powerful symbol and as decorative field. Macdonald’s recent work reverses this traditional foreground and background. She seems to suggest the flower as figure: after all, like the body itself, a bloom suggests brevity—of life, its tenuous beauty. And yet Macdonald’s painted photographs and collages evoke timelessness, an insistence upon beauty arising from and protecting us from chaos, a talisman against darkness. Still, the darkness is present—in the opaque black wax of a rupturing bloom, in the ghostly outline of a vine etched white-into-white, its milky viscosity.

In recent pieces where her pattern work is foregrounded, the material becomes insistent. The viewer begins to notice the wax, to question its relationship to the subject matter. What is the connection between human, flower, and bee (the producer of the wax Macdonald uses called to mind through hexagonal patterning)? It is the bee who travels between flowers, reproducing them but also harvesting pollen for its own use. So does Macdonald reproduce these subjects—flowers and the female form... and in the process seems to steal material for her own mysterious purpose.

Macdonald uses both chemical and physical processes in her art: she photographs, she collages, she paints with oils and wax, she marks her images, sometimes scars them. But this making art upon art she does with the sensitivity of a poet. She is not about destruction but about extraction: she brings to the surface the worlds that hide within and behind. This is already an interior world, a dreamt world, an elusive world half-remembered, available to multiple interpretations, never-fully-grasped. Figure and flower, photograph and wax: Macdonald’s hybrid art makes space for the in-between-ness of experience. We are neither one thing nor another, not fully our past and its traumas, not fully the beauty we seek—we are all of these, accreted layer by layer over years. And we are the space between.

CONTACT:

Leah Macdonald

498 Ripka St

Philadelphia, PA 19128

610.247.9964

leahwax1@gmail.com

Links to Purchase Art: